Megan Kirkwood is a fellow at Tech Policy Press.

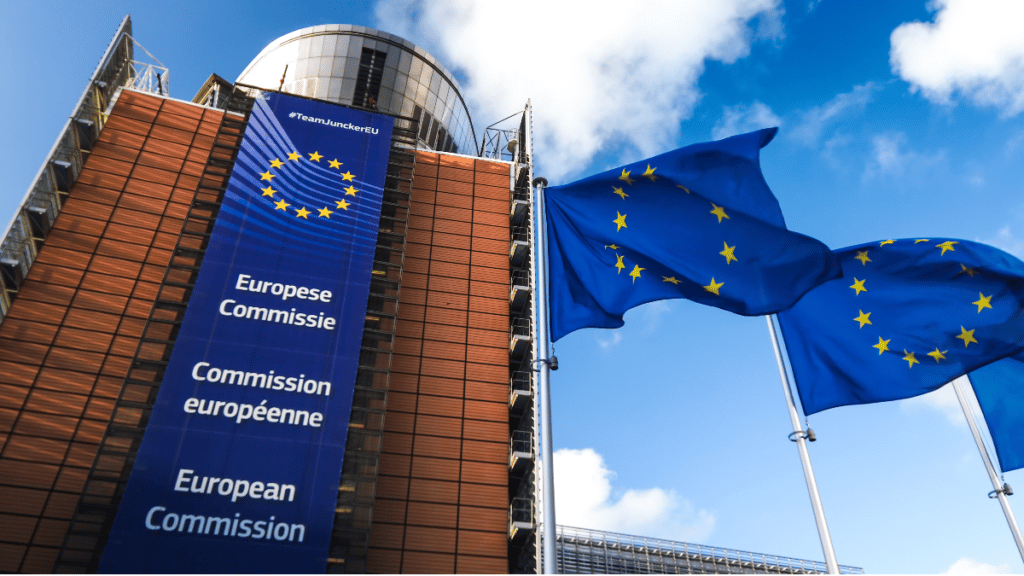

Flags of the European Union aside a European Commission building.

The European Digital Markets Act (DMA) has been in force since March 6, 2024, with the European Commission first announcing its initial list of designated gatekeeper firms and their core platform services on September 6, 2023. The gatekeepers that must comply with the law are Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft, with the online travel agency website Booking.com being designated later. The core platform services that fall under the obligations and prohibitions of the law include TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, Google Search, Android OS, iOS, Amazon Marketplace, and more, with a total of 23 services coming under the legislation.

In the text of the law, core platform services include online intermediation services (such as Booking.com), search engines, social networks, video-sharing platforms, messaging services, operating systems, web browsers, virtual assistants, cloud computing services, and online advertising services. However, the law allows for the Commission to add new core platform services, and the Commission has continually debated whether AI should be explicitly added to this list or if the DMA already sufficiently captures AI applications integrated into core platform services.

Is AI covered under the DMA?

There has been continued interest in bringing integrated AI applications under the DMA. On October 14, 2024, the Commission launched a call for tenders to “identify and outline the recent and expected developments in emerging technologies, such as generative AI, and assess the possible impact of these emerging technologies on the DMA implementation.” The Commission had also previously published a policy brief on competition in generative artificial intelligence and virtual worlds on September 19, 2024. The brief outlined that:

There are two main ways in which the DMA will be relevant for generative AI services. First, a generative AI player may offer a core platform service and meet the gatekeeper requirements of the DMA. Second, generative AI-powered functionalities may be integrated or embedded in existing designated core platform services and therefore be covered by the DMA obligations. Those obligations apply in principle to the entire core platform service as designated, including features that rely on generative AI.

The brief pointed out that vertically integrated gatekeepers like Google, Amazon and Microsoft often offer both “AI foundation models” as well as cloud computing or other applications that fall under the DMA, such as search engines, which may have integrated generative chat interfaces. However, the brief did not detail potential changes those integrated services might need to make to bring them into compliance.

Taking its investigation into integrated services further, the latest round of DMA compliance workshops held this year asked gatekeepers to present how AI is integrated into their core platform services and how this complies with DMA obligations. However, these workshops revealed the shortcomings of the current approach to regulating AI through the DMA.

Most conversations at the workshops concerned Article 5(2), which requires gatekeepers to obtain explicit consent before cross-utilizing personal data from core platform services in other services. This is relevant to AI development, as gatekeepers building AI models can access masses of data through publicly available sources and from their proprietary services. This data may comprise personal data, though gatekeepers maintain their compliance with the DMA through introducing user opt-out requests, or, as Meta argued in its workshops, have either excluded personal data from model training or de-identified and aggregated data so that it could no longer be considered personal data. Thus far, the massive data advantages held by gatekeepers have not been addressed through the DMA.

Big Tech platforms maintain ecosystem advantages, meaning that users interact with their services when they are integrated into other popular services. For example, Google Search maintains a global market share of roughly 90%, and therefore, integrating its AI Overview and AI Mode services presumably gives Google a massive ecosystem advantage for its Gemini model. While the DMA can prevent users from having to accept one service in order to use another, potentially undermining this ecosystem advantage, Ayşe Gizem Yaşar, Assistant Professor at the London School of Economics, and coauthors point out that under Article 5(8) this only applies across core platform services. Therefore, undermining this ecosystem advantage may be out of reach until generative AI is added as a core platform service.

The European Commission consults on AI and the DMA

The DMA mandates that by May 3, 2026, and subsequently every 3 years, the Commission must evaluate the DMA to ensure it is achieving its aim of creating fair and contestable digital markets, and whether the regulation needs to be amended to do this. This can be done by modifying the list of core platform services or the obligations laid down in Articles 5, 6 and 7 and their enforcement. To do this, the Commission has launched a consultation on the first review of the DMA, which includes a dedicated questionnaire on AI, which aims to understand if “the DMA can effectively support a contestable and fair AI sector in the EU.” The consultation closed on September 24, 2025.

The questionnaire regarding AI is particularly geared toward business users to understand the “bottlenecks or obstacles” to developing competing models or AI products and services. In particular, it aims to understand obstacles preventing “access to relevant inputs and/or distribution channels (e.g., computing capacity, (personal) data, cloud services, foundational models, search functionalities, operating systems, browsers, user-facing services, etc).”

Adding AI as a core platform service has previously received support from representatives of France, Germany, and the Netherlands, who also advocated for “designating certain cloud service providers under the qualitative thresholds of the DMA, given the importance of computing power for large AI models.” Cloud computing is dominated by Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud, and is “a core dependency in building large-scale AI.” Indeed, those same hyperscalers are best placed to benefit from the use of AI due to cloud lock-in and ecosystem dependencies.

Thus, the question remains whether the Commission should designate generative AI as a core platform service (meaning large language model-based chatbots or image generation services), concentrate on designating cloud computing, which is already a core platform service, or both?

What would designating generative AI achieve?

According to Yaşar and her coauthors, adding generative AI as a core platform service is necessary to rebalance contestability in an AI market currently ruled by those who can gain the most access to computing power and maintain first-mover advantages. While provisions of the DMA, such as data sharing or protection of business users against unfair terms, could introduce some contestability, as it stands, “any generative AI behemoths that do not provide any other core platform service cannot be designated as a gatekeeper under the DMA.” This leaves dominant players like OpenAI entirely unscathed by the DMA.

The AI market is ruled by those holding data and ecosystem advantages. Indeed, the authors point out that Recital 3 of the DMA explicitly articulates how “control over whole ecosystems allows gatekeepers to leverage their advantages from one area of activity to the other, which in turn reduces contestability.” Ecosystem integration “further muddies the distinctions between different services when it comes to data processing practices. As services and data become increasingly intertwined, it becomes difficult for a user to switch between platforms and transport their data and projects.” Thus, users become increasingly stuck inside the ecosystem, and those services become embedded within each other. The authors argue that AI applications are being integrated into these ecosystems, “combining search, email, personal assistants, and many others, with generative AI models through a user interface,” and massively benefiting from this ecosystem advantage, undermining competition and contestability.

To fix this, they argue that generative AI must become a core platform service because Article 5(8), which bans users from being forced to “subscribe or register with” other services offered by the gatekeeper, only applies to other core platform services. Therefore, users would have to be presented with a choice before being registered for a service, and must be able to access services as standalone applications. With the news that Google is planning to integrate its Gemini language model into Chrome, YouTube, Maps, and Calendar, would adding generative AI to the DMA give users more control?

Alba Ribera Martínez, a visiting professor at the Brussels Study Center, has publicly stated her opinion that generative AI should not be added as a core platform service. Instead, she has argued in favor of “actively enforcing existing DMA provisions and accommodating generative AI as an embedded functionality or technology.

Her argument stems from the fact that the current obligations and prohibitions listed in Articles 5 to 7 may not be well-suited to generative AI, with most of the rules not applicable to standalone generative AI services. She adds that bringing generative AI under the DMA will likely introduce “legal and interpretative challenges” for the enforcer, particularly considering “the data-related obligations mandating the siloing of gatekeeper data.” Article 5(2) bans the cross-use of data between services, which she argues is unclear when applied to gatekeepers processing large amounts of data to power generative AI services.

She also argues that enforcement of 5(2) is fundamentally incompatible with the way AI systems are built. Assuming “that the designation of gatekeepers would take place once those generative models had gone through the three development stages,” data will have already been collected, combined and processed. Therefore, “the risks arising from the pre-training stage would remain, irrespective of the DMA’s application.” In other words, the impact of 5(2) would be very limited, as models would already be built before DMA obligations would take effect.

Further to this, Martínez states that “the implementation of Article 5(2) DMA interferes with the data combinations and cross-uses that most foundation models feed on to deliver the capabilities embedded into genAI services,” and designating generative AI “may provoke more undesired consequences” than benefits. For example, she writes that gatekeeper AI providers may “outsource their foundational model development or limit the features they will roll out in the EU altogether,” meaning “European consumers would not enjoy nor interact with functionalities tailored to their own needs, preferences and territorial idiosyncrasies.”

Beyond recognizing the possibility of adding potential gatekeepers like OpenAI if generative AI were added as a standalone service, Martínez argues that generative AI is best understood as “an embedded functionality within most of the gatekeepers’ existing (and designated) services. They can, thus, be considered one and the same as those categories of CPSs.” She advocates for designating services under already existing core platform service categories like cloud computing or virtual assistants, which could “capture some of the impending problems surrounding the development and deployment of genAI services, notably self-preferencing opportunities open to their developers.”

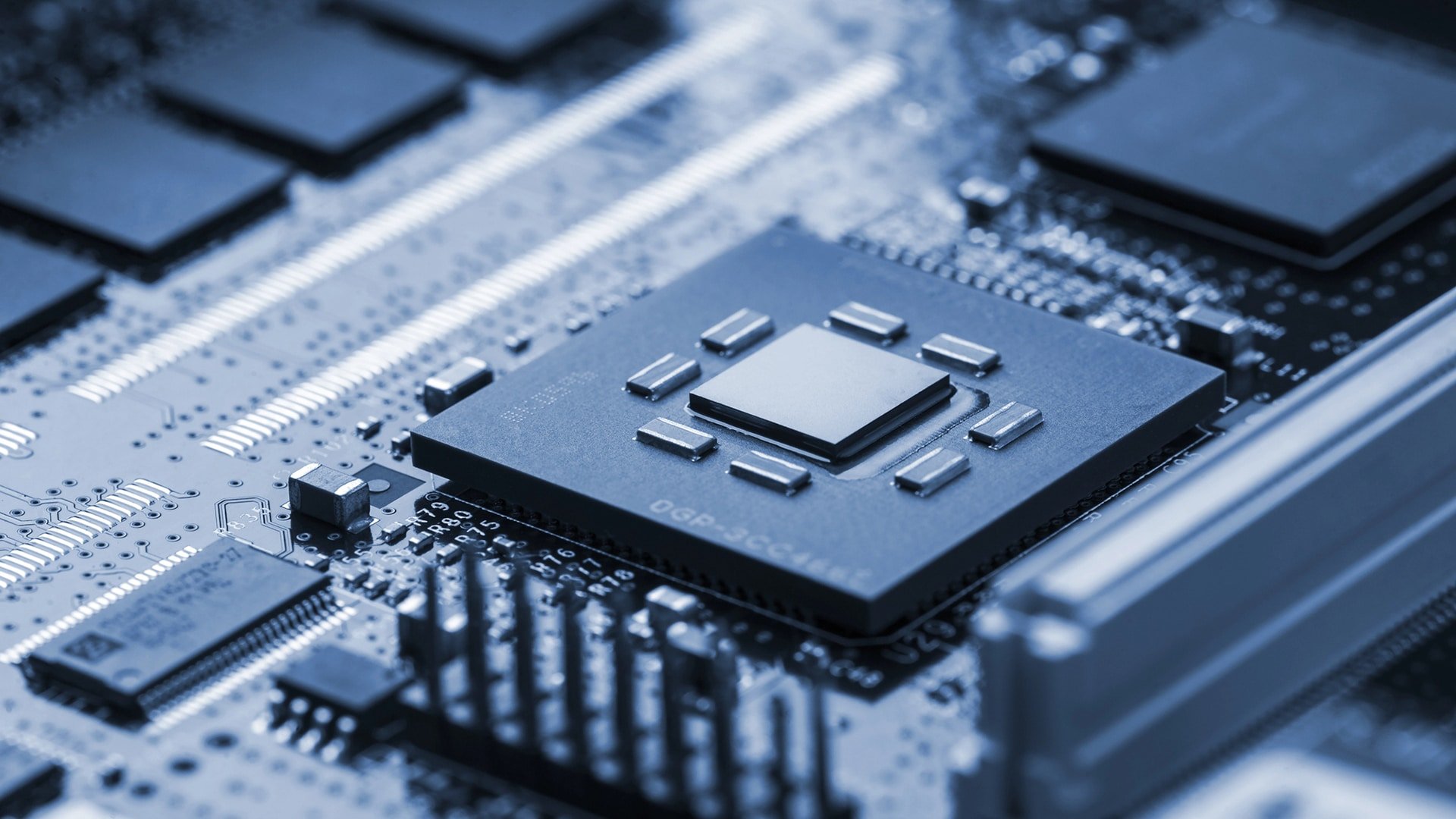

Designating the Cloud

When analyzing the competitive dynamics of AI markets, experts point to the need to look upstream at the concentration of computing power. Indeed, Max von Thun and Daniel A. Hanley at the Open Markets Institute write that “[w]hile there may be plenty of ‘downstream’ competition when it comes to the practical deployment of AI through various applications and services, this diversity is built on a consolidated set of ‘upstream’ inputs including foundation models, cloud computing, semiconductors, and data.” The same cloud giants that control the compute control downstream applications through cloud dependency, as well as financial lock-in through partnerships, investments and acquisitions. Thus, tackling concentration in the cloud may see downstream effects in AI markets.

Cloud computing is already listed as a core platform service under the DMA, and thus, designating cloud services would be a much faster process than creating a new core platform service category. Michelle Nie, a tech policy researcher formerly with the Open Markets Institute, says the EU should designate cloud providers to tackle the infrastructural advantages held by gatekeepers. Indeed, she has previously written for Tech Policy Press that doing so “would help address several competitive concerns like self-preferencing, using data from businesses that rely on the cloud to compete against them, or disproportionate conditions for termination of services.”

While this would improve competitive conditions for both cloud providers and AI services, Nie has also been firm that structural remedies like “divestment of a line of business from the rest of the company, […] can be helpful in tackling concentrated tech power by removing incentives and conflicts of interest that cause them to behave anticompetitively.” AI Now Institute’s Kate Brennan, Amba Kak, and Dr. Sarah Myers West have suggested various structural remedies, such as preventing cloud providers from also participating in the market for foundation models, which would much more directly prevent ecosystem advantages from taking hold, or blocking Big Tech AI investments, mergers and acquisitions. These would more completely prevent conflicts of interest for the biggest players operating at points along the AI value chain.

Introducing contestability and fairness, the stated goals of the DMA, into digital ecosystems increasingly relied on by private and public institutions could not be more critical. The Commission may need to consider an “all of the above” approach, thus tackling data and distribution advantages maintained by gatekeepers, as well as upstream concentration.