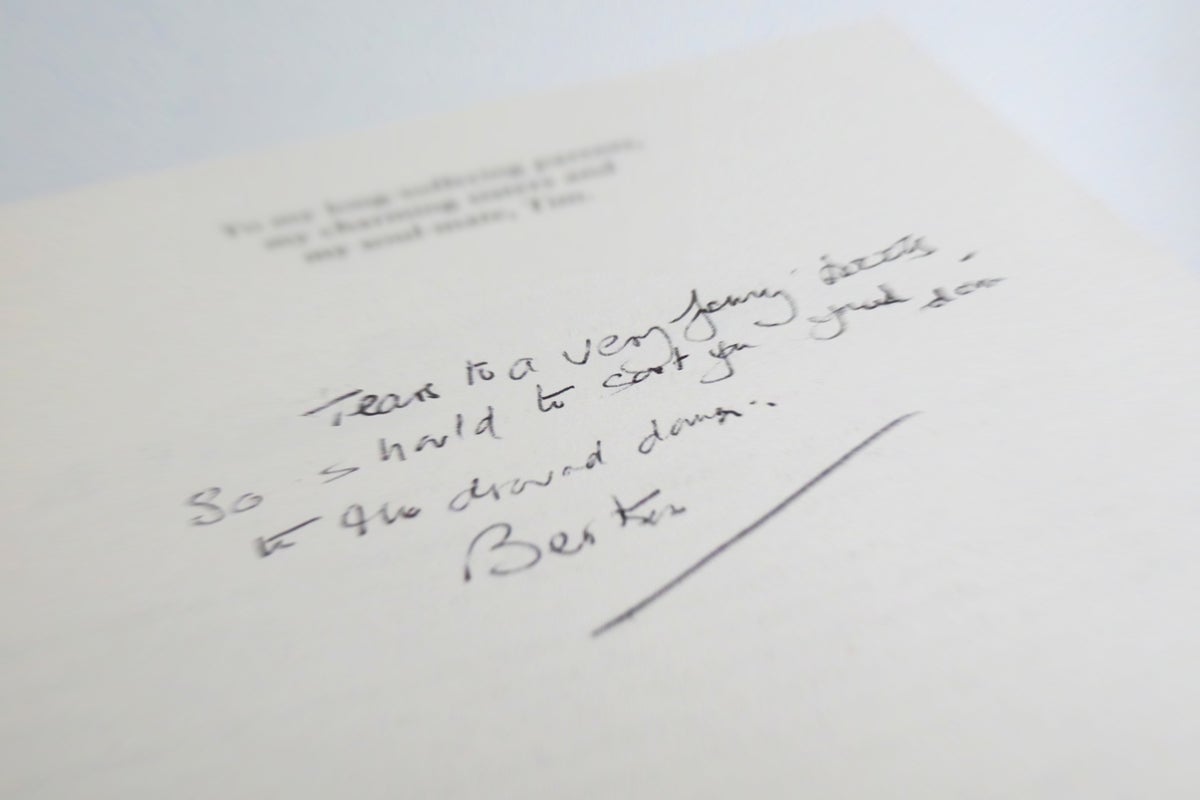

TTwo days before my father died, he gave me a book. It was my 28th birthday, and in front of it was an 18-word note he had written a few days earlier. But I couldn’t understand it.

I couldn’t ask him what it said because by the time I saw him he was asleep and heavily medicated. The cancer had spread from his brain to his bones and down to his lungs, and the only words I would hear him say again were “I hope Ireland win.” (He briefly rose from his delirious sleep to intervene in an argument I was having with my sister across his bed about whether he wanted Ireland or France to win the final match of that year’s Six Nations. Ireland won by two points.)

Later, when I showed the note to my mother and sister, we were able to decipher the first line: “This is a very funny book,” but the rest – the most important part – seemed unreadable.

It took me years before I felt ready to read the book he gave me, but I kept it by my bedside through several moves. I would go back to it and think about these 18 words, and I would sometimes show it to close friends or family, but none would offer me a deeper understanding.

The book was Dear Lupine: Letters to a Wayward Sona collection of father-son correspondence from the late motoring journalist Roger Mortimer, and I hoped reading it would give some idea of what my own father had been trying to say. The book was indeed funny, as its first line suggested, but the rest of the note remained incomprehensible.

In 2023, seven years after my father passed away, artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT began offering the ability to interpret images you upload. They could translate text or help you understand what you were looking at, so I decided to take a photo of the words and see how it turned out.

The AI immediately recognized that it was a personal inscription, without any prior context, but the words it spoke were gibberish.

Tears for a very funny Dacts

So I should sort you out

To the manure of the ground

Best

The AI explanation was equally confusing. “‘Beste’ is a very common closing in Dutch and German, meaning ‘Best regards’ or ‘Best regards,'” he explained to me.

My father spoke neither language and I knew his nickname: Bertie, taken from our last name. I also thought the first word was a misspelling of “Here’s”, and that the word “Dacts” was almost certainly “Book”, so I corrected the AI with my interpretation of its penmanship.

With this new information, he came up with a new decryption of the second two lines.

So I should sort you out

at dawn.

My father was many things – a rodeo rider, a skydiver, a currency seller – but he was not a poet. It seemed unlikely that he would make his first attempt on his deathbed, with the alliterative final words of the inscription.

But he was an avid reader of poetry, so perhaps this was one of his favorite lines. Nothing came up when I Googled these words, and when I asked ChatGPT it came back with this passage:

He walked the shore, until the drowned dawn,

Where the morning light was lost beneath the waves.

When I asked who wrote it, the chatbot apologized for not being able to find “any reliable source attributing these lines.” It was a hallucination.

Soon after, I heard about a project involving Google DeepMind, in which researchers restored half-destroyed ancient texts by training AI on thousands of ancient Greek inscriptions to predict the missing text.

Something like this might work if I had more of the handwritten texts that my father had written in a more lucid state. The only problem was that I didn’t have any. The only thing he left me in his will was his extensive book collection, over a thousand titles in total. Aside from one or two first editions, the books themselves aren’t worth much. The real treasure, at least for me, were the bookmarks. Each one was a memento of his life: old boarding passes, theater tickets, business cards, receipts.

I looked through them all, looking for something he might have jotted down until I finally found what appeared to be a shopping list. During my research, I also came across some old birthday cards he had written to me, but in total I had no more than two dozen words. It wasn’t enough. I needed a larger data set.

Finally, this summer, there was a breakthrough. It came in the form of a stack of letters written to his sister decades ago while he was working as a jackeroo in Australia. My cousin had come across them and sent them immediately.

After passing these letters to ChatGPT and Gemini, the AI was able to analyze his idiosyncratic writing style: the looped shape of his consonants and rushed vowels.

I also provided more context on when and where the note was written, and here is the new interpretation:

This is a very funny book.

It would therefore be necessary [help] to sort your descent

in the gloomy humidity

Bertie

ChatGPT noted that February in Hampshire where he lived and where I spent more and more time with him, had been wettest since records began. He also hated the end of the rainy winter in England, so the third line seems to be exactly what he wrote.

Building on this success, I decided to try other forms of AI to see if they would uncover new information about my father. Google Gemini new deep search feature is able to autonomously sift through your emails and documents to provide analysis on any topic within them.

I asked him to review all the digital interactions I had with my father, and he came up with a “scientific analysis of direct email correspondence between Anthony Cuthbertson and his father, Malcolm Cuthbertson.”

It didn’t add much more than reading the email exchanges I could have contributed. The introduction to the unnecessarily long 3,500-word thesis stated: “The recovered digital record provides a structured narrative of a father-son relationship in the context of significant life events, including international travel, high-stakes academic deadlines, philosophical divergences, and terminal illnesses. »

However, one thing I never thought about was that he used his work email address in all of our personal communications.

“This integration of professional and family identities suggests that Malcolm viewed his corporate life – the source of his international experience and network – as inseparable from his role as a father, ensuring that his son was aware of both sides of his world.”

But he also missed some of the finer points that he couldn’t know just from our emails. He was talking about my “intellectual prowess” after my father congratulated me on my A-level math score, unaware that it was a retake and that I only got a B. He lacks real-world context – a fundamental flaw of AI.

Other AI tools have offered people the ability to speak directly with their deceased loved ones via so-called “grief bots” or “dead bots.” A growing number of startups are developing chatbots that use the same LLM (Large Language Model) technology as ChatGPT and Gemini – trained on their digital interactions – in an attempt to simulate deaths.

I visited a first version of these shortly after my father died, and I wasn’t convinced. They seem to provide more evidence that a person is gone, rather than offering hope that they can be resurrected using a computer.

Others found these services disappointing and scary, while some even argued that deceased people’s data should be protected by law from AI.

Legal scholar Victoria Haneman argued in a recent article titled “The Law of Digital Resurrection” that the deceased do not have legal protections against the use of their messages, photos and voice recordings to create chatbots, avatars or AI versions after their death.

“The digital right to die has not yet been recognized as an important legal right,” she said. wrote in the Boston College Law Reviewcalling for a “time-limited right to deletion of personal data” which gives descendants the option to destroy all digital archives within 12 months.

There may be no digital archive that could provide a fully accurate interpretation of my father’s last words. The second line remains largely a mystery, and that’s okay. I knew this attempt might be in vain. But the research uncovered bookmarks and other relics that I might never have found, and helped me understand him in ways that I may never understand his final grade.

Perhaps future iterations of AI technology will be more useful. Or maybe my father’s parting words are exactly what they seem: a largely absurd note, written by a dying, morphinized spirit offering his son a final birthday present, and a riddle that cannot be solved.