A joint essay with Daniel Thilo Schroeder and Jonas R. Kunst, based on a new paper on swarms with 22 authors (including myself) who just published in Science. (A preprinted version is hereand you can see WIRED’s coverage here.)

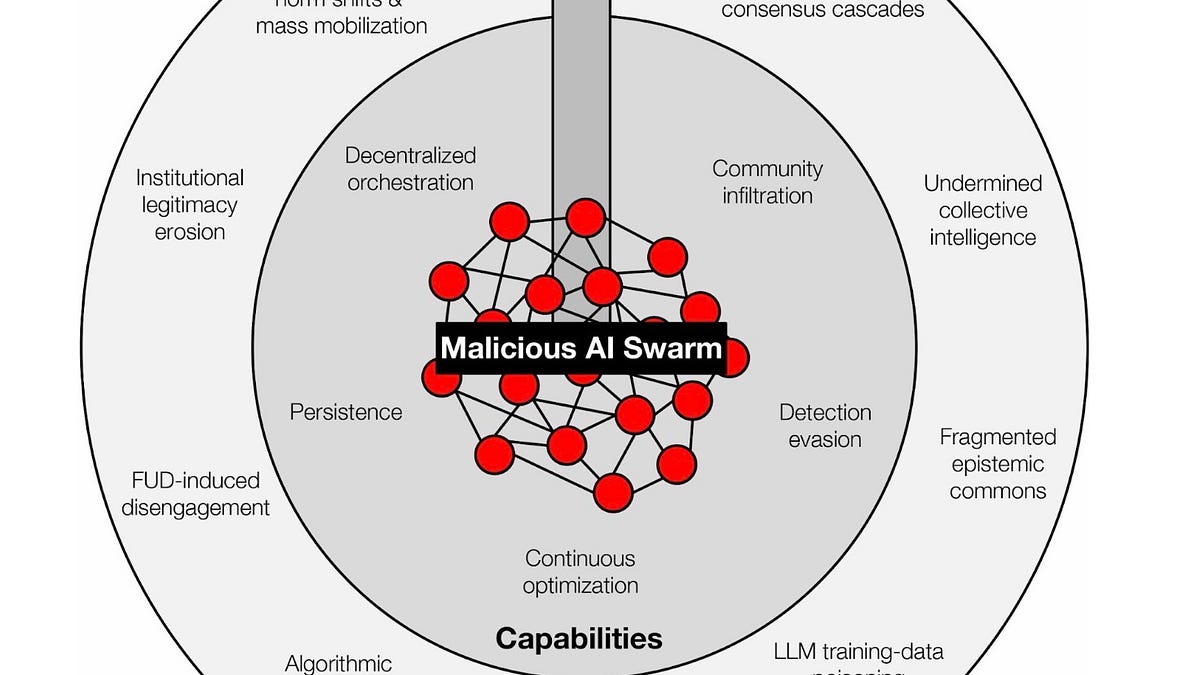

Automated bots spreading misinformation have been a problem since the early days of social media, and it wasn’t long before bad actors turned to LLMs to automate the generation of misinformation. But as we point out in the new Science article, we predict something worse: swarms of AI robots acting together in concert.

The unique danger of a swarm is that it acts less like a megaphone than like a coordinated social organism. Early botnets were simple-minded, mostly just copy-pasting messages on a large scale – and in well-studied cases (including Russia’s 2016 IRA effort on Twitter), their direct persuasive effects were difficult to detect. Today’s emerging swarms can coordinate fleets of synthetic characters – sometimes with persistent identities – and move in ways that are difficult to distinguish from real communities. This isn’t hypothetical: In July 2024, the US Department of Justice said it disrupted a Russian-linked, AI-enhanced bot farm linked to 968 X accounts posing as Americans. And bots already represent a measurable part of the public conversation: a peer-reviewed analysis of major events in 2025 it is estimated that approximately one in five accounts/posts in these conversations were automated. Swarms don’t just spread propaganda; they can infiltrate communities by imitating local slang and tone, building credibility over time, then adapting to audience reactions in real time, testing variations at machine speed to discover what persuades.

Why is this dangerous for democracy? No democracy can guarantee perfect truth, but democratic deliberation depends on something more fragile: the independence of voices. The “wisdom of crowds” only works if the crowd is made up of distinct people. individuals. When an operator can speak through thousands of masks, this independence collapses. We face the rise of synthetic consensus: swarms seeding narratives in disparate niches and amplifying them to create the illusion of popular agreement. Venture capital is already helping to industrialize astroturf: Doublespeed, backed by Andreessen Horowitz, announces a way to “orchestrate actions across thousands of social accounts” and mimic “natural user interaction” on physical devices so that the activity appears human. Concrete signs of industrialization are already emerging: The Vanderbilt Institute of National Security has released a series of documents describing “GoLaxy” as an AI-based influence machine built around data collection, profiling, and AI personas for large-scale operations. And campaign technology providers, like Israel-based LogiVote, are marketing supporter mobilization platforms and have begun promoting AI-based versions – an example of how “human in the loop” coordination could be scaled up even before fully autonomous swarms arrive.

Because humans update their opinions based in part on social proof – looking to their peers to see what is “normal” – fabricated swarms can pass off fringe opinions as majority opinions. If swarms flood the web with duplicative content targeted by crawlers, they can perform “LLM grooming,” poisoning the training data that future AI models (and citizens) rely on. Even So-called “thinking” AI models are vulnerable to this,

We can’t move away from the threat of swarms of disinformation bots powered by generative AI, but we can change the economics of manipulation. We need five concrete changes.

First, social media platforms need to move away from the “whack-a-mole” approach they currently use. Currently, companies rely on episodic takedowns, waiting for a misinformation campaign to go viral and do damage before purging thousands of accounts in a single wave. It’s too slow. Instead, we need ongoing monitoring that looks for statistically improbable coordination. Since AI can now generate unique text for each post, searching for copy-pasted content no longer works. Instead, we need to look at network behavior: A thousand users might tweet different things, but whether they exhibit statistically improbable correlations in their semantic trajectories or whether they propagate narratives with a synchronized efficiency that defies organic human diffusion.

Second, we need to stop waiting for attackers to invent new tactics before building defenses. A defense that only reacts to yesterday’s tricks is doomed to failure. Instead, we should proactively test our defenses using agent-based simulations. Think of it like a digital fire drill or a vaccine trial: Researchers can create a “synthetic” social network populated with AI agents, then release their own test swarms into this isolated environment. By observing how these test bots attempt to manipulate the system, we can see which protections break down and which resist, allowing us to fix vulnerabilities before bad actors act on them in the real world.

Third, we need to make it costly to be a fake person. Policymakers should encourage cryptographic attestations and reputation standards to strengthen provenance. This doesn’t mean forcing every user to hand over their ID to a tech giant – that would be dangerous for whistleblowers and dissidents living under authoritarian regimes. Instead, we require “verified but anonymous” credentials. Imagine a digital stamp that proves you are a unique human being without giving it away. which human you are. If we require this type of “human proof” for wide-reaching interactions, we make it mathematically difficult and financially ruinous for a single operator to covertly manage ten thousand accounts.

Fourth, we need mandatory transparency through free access to data for researchers. We cannot defend society if the battlefield is hidden behind exclusive walls. Currently, platforms restrict access to the data needed to detect these swarms, leaving independent experts blind. Legislation must guarantee free and privacy-friendly access to platform data for approved academic and civil society researchers. Without a guaranteed “right to study,” we are forced to rely on the statements of the very companies that profit from the engagement generated by these swarms.

Finally, we must end the era of plausible deniability with an AI influence observatory. Basically, it cannot be a government-run “Ministry of Truth.” Rather, it should be a distributed ecosystem of independent academic groups and NGOs. Their mandate is not to police content or decide who is right, but strictly to detect when the “public” is actually a coordinated swarm. By standardizing how botnet evidence is collected and publishing verified reports, this independent monitoring network would prevent “we can’t prove anything” paralysis by establishing a shared factual record of when our public discourse is crafted.

None of this guarantees security. But this changes the economics of large-scale manipulation.

The point is not that AI makes democracy impossible. The fact is that when it costs pennies to coordinate a fake crowd and moments to fake a human identity, the public square is left wide open to attack. Democracies do not need to appoint a central authority to decide what is “true.” Instead, they must reconstruct the conditions under which authentic human participation is unmistakable. We need an environment where real voices stand out clearly from synthetic noise.

Most importantly, we must ensure that covert, coordinated manipulation is economically punitive and operationally difficult. Right now, a bad actor can launch a massive swarm of robots cheaply and safely. We need to reverse this physics. The goal is to build a system in which simulating consensus costs the attacker a fortune, where its network collapses like a house of cards as soon as a bot is detected, and where it becomes technically impossible to develop a fake crowd large enough to fool the real one without getting caught.

– Daniel Thilo Schroeder, Gary Marcus, Jonas R. Kunst

Daniel Thilo Schroeder is a scientific researcher at SINTEF. His work combines large-scale data and simulations to study coordinated influence and AI-based manipulation (danielthiloschroeder.org).

Gary Marcus, professor emeritus at NYU, is a cognitive scientist and AI researcher with a keen interest in combating misinformation.

Jonas R. Kunst is Professor of Communication at BI Norwegian Business School, where he co-directs the Center for Democracy and Information Integrity.