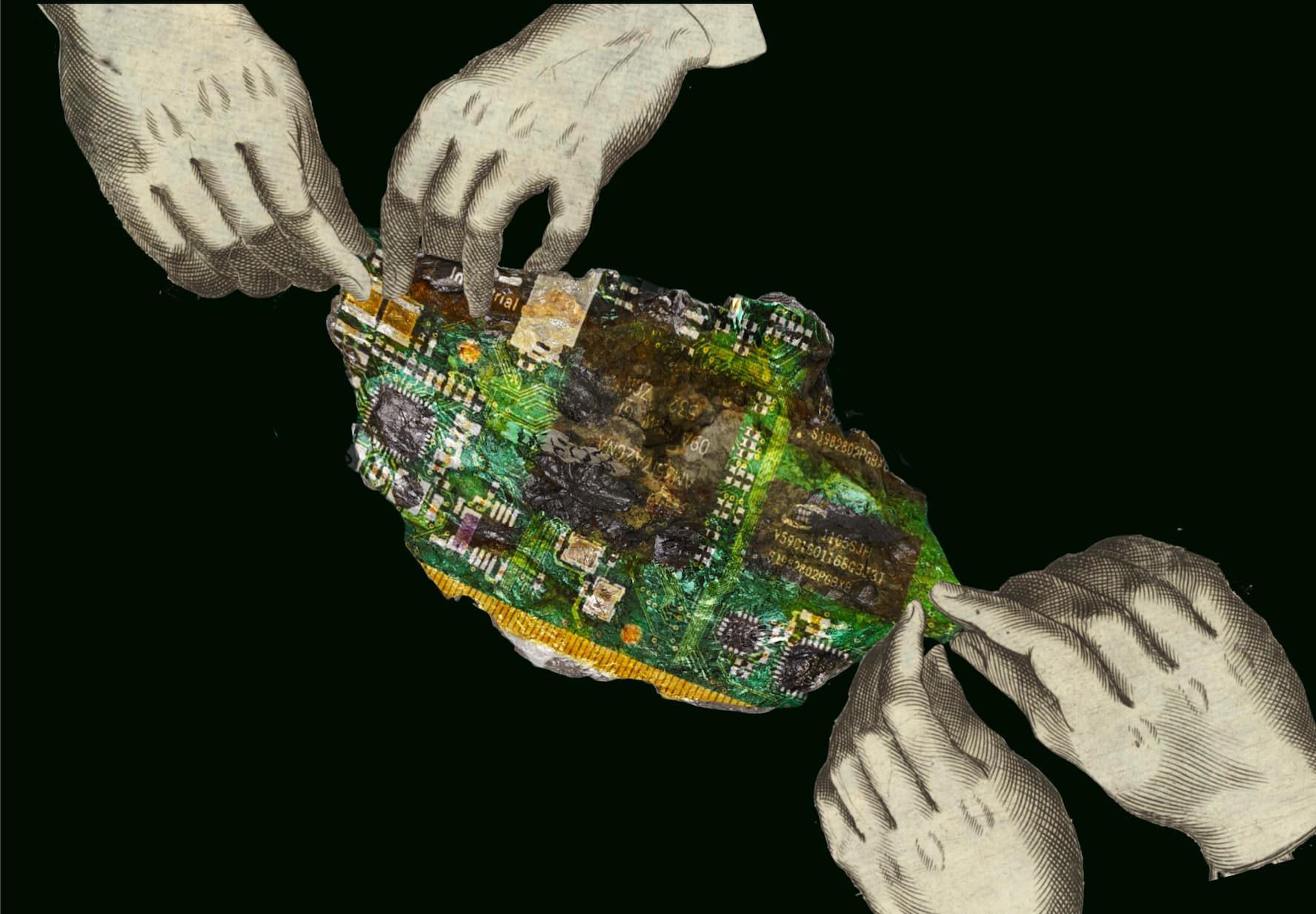

Everyday tools like artificial intelligence (AI) and social media algorithms aren’t just powered by technology—they require human workers to sort through our content, labeling, tagging, transcribing, and processing data. Platforms to support this work have existed since at least 2005, but outsourcing labeling, often to workers in the Global South, has become increasingly lucrative over the past few years due to the increasing demand for data. In fact, the World Bank estimates there are between 150 and 430 million data laborers whose work ultimately drives cutting-edge technological development.

These individuals, who often work in “digital sweatshops,” consistently report poor working conditions, exploitation, and forms of psychological distress. In Africa and South and Southeast Asia, it is not uncommon for workers to work up to 20 hours a day, sifting through 1,000 cases in a shift. While workers have formed unions and advocacy groups, unclear business process outsourcing (BPO) practices, a lack of regulatory guardrails on gig platform labor, and the uncertain future of data work limit the capacity of data laborers to organize and demand fair and transparent working conditions.

What this work looks like

Annotated data sets are used to train AI models that learn patterns to then generate content, make predictions, or complete classification tasks. Data annotation, processing, and evaluation are also key components of content moderation systems that filter out graphic, harmful, and hateful content from platforms. Making micro-decisions throughout the data pipeline requires contextual human understanding and is often outsourced to the Global South through BPO and digital labor platforms. In some cases, data laborers interact with toxic, graphic, and hateful content under distressful and exploitative working conditions—ironically, to train systems that shield users from the same disturbing content.

The conditions surrounding this work are cause for concern. Oxford’s Fairwork project surveyed over 700 workers who work on digital labor platforms, and concluded that none of the 15 assessed platforms score better than the “bare minimum” on fair pay, conditions, contracts, management, and representation. A 2025 Equidem survey of 76 workers from Colombia, Ghana, and Kenya reported 60 independent incidents of psychological harm, including anxiety, depression, irritability, panic attacks, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance dependence. Workers also noted forced unpaid overtime, no fixed salary, and instances of companies withholding payments.

Contract workers in Ghana report “grueling conditions” from moderating disturbing content: murders, extreme violence, and sexual abuse, for example. One former content moderator said he read up to 700 sexually explicit and violent pieces of text per day, with the psychological toll of his work causing him to lose his family. Due to this exposure, many workers experience depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

BPO practices obstruct meaningful accountability

Since data workers are often subcontracted by multinationals, such as Big Tech companies, through third-party vendors and agencies, workers often do not possess clear avenues for reporting grievances and unfair labor practices. Despite reports from investigative journalists and research institutes about psychological trauma and exploitative working conditions in certain forms of data work, some companies manage to avoid accountability by leveraging the ambiguity around which entity bears responsibility for maintaining adequate labor conditions. These platforms often do not provide clear dispute mechanisms that workers can use to elevate their concerns. Workers also frequently do not know which systems their work will train or build: One investigation found that Kenyan data labelers working for the platform Remotasks were unaware it was a subsidiary of ScaleAI, a company that provides data to Big Tech companies. This problem extends to the entire industry: Opaque supply chains limit workers’ ability to challenge exploitative labor practices.

Challenges to worker exploitation

Several lawsuits, researchers, and grassroots organizers have pushed back against these labor practices. For example, content moderators have formed the African Content Moderators Union and the Global Trade Union Alliance of Content Moderators to fight for fair wages and safe working conditions across borders. In Kenya, workers have launched the Data Labelers Association to fight for better working conditions, fair pay, and mental health support. That said, many individuals face threats of retaliation or actual retaliation. In Turkey, content moderators alleged they were fired by a company providing outsourcing services to TikTok for their attempts to unionize. Research and advocacy groups also hope to document and elevate related concerns. For example, the “Data Workers Inquiry” is a global research initiative that empowers data workers to be advocates and community researchers. Another example is Turkopticon, an advocacy and mutual aid group that organizes to better the working conditions of Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers. Smaller data labeling platforms, such as Karya, also provide an ethical alternative to traditional data labeling work by promising fair wages and economic opportunity to rural Indians.

Lawsuits and investigations have also been initiated in various jurisdictions. In Kenya, a court ruled that a platform could be sued for its mass layoffs of content moderators who alleged exploitation and deteriorating mental health. The Colombian Ministry of Labor launched an investigation at the end of 2022 into Teleperformance, a third-party vendor providing data to TikTok, for exposing workers to distressing content while paying them as little as $10 a day. Meta currently faces lawsuits in Ghana, where moderators working for Majorel, a BPO company, allege terrible working conditions that include cramped living quarters and exposure to depiction of murders, extreme violence, and abuse. Despite these legal efforts, this whack-a-mole approach of filing lawsuits and investigations one at a time cannot effectively prevent structural labor abuses from occurring.

The implications of automated content moderation on labor and inclusive technological development

While workers organize and challenge exploitative labor practices in court, companies have focused on further developing machine learning algorithms and tools to detect potentially harmful content and assess the privacy and social risks of products. They hold great promise in reducing the psychological burden of data labor, but companies should not treat automated content moderation and annotation as substitutes for establishing fair and transparent labor practices.

Through machine learning classifiers, hashing (e.g., removing images containing child sexual abuse material), and keyword filters, AI-assisted content moderation aims to replace a portion, or all, of human labor involved in content moderation. These tools have existed in some form for a while; examples include the Washington Post’s ModBot, which was launched in 2017, as well as Google’s Jigsaw toxicity-reducing API, a free and open-source tool to assist moderators in managing online toxicity and harassment. AI models that support content moderation may reduce the psychological and emotional burden of data work on humans. They can also be deployed at scale, allowing moderation to occur quickly and efficiently.

On the other hand, automated content moderation introduces concerns around contextual understanding, accuracy, and transparency in decision-making. Biased data labeled by humans may be reinforced at scale by algorithms. AI models trained on historic datasets are also unable to account for culturally and context-specific forms of expression that evolve over time. This is especially true in data-sparse contexts, such as those involving low-resource languages. For instance, algorithms would likely underperform when working in contexts with code mixing, algospeak (a form of resistance to evade content moderation algorithms), and new linguistic forms, such as the Kiswahili variation Sheng. Malicious actors have also leveraged linguistic shortcomings in content moderation systems to show explicit content from religious queries. One study that evaluated the Jigsaw toxicity-reducing API reported high false positives from automated content moderation. Another document leaked from Facebook noted that algorithms incorrectly removed and flagged nonviolent Arabic content as “terrorist content” 77% of the time, which censored reporting of alleged war crimes. Transparency and explainability in content moderation decisions are already limited and inconsistent, a problem that may be further amplified with automated content moderation due to algorithms’ inability to consistently and faithfully explain their reasoning.

Despite their limitations, some forms of automated task completion and content moderation may be useful for low-wage data work that involves toxic and harmful content. Beyond complete automation of data tasks, AI can also be used to pre-process data and blur potentially graphic images for data laborers, even in contexts other than content moderation.

Given these trends, stakeholders involved should take decisive action to promote transparency and ethical labor practices in data labeling work. International bodies should clarify responsibility around worker protection in BPO contexts, pursuant to international principles and discussions around fair labor, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and documents released from the International Labour Conference’s standard-setting committee on Decent Work in the Platform Economy. Given the global nature of data labor, cross-border cooperation is necessary. Regional bodies such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the African Union (AU), and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) should work to establish binding directives around the rights of data laborers. Some countries, such as Argentina and Mexico, have made strides in developing guidelines around gig work. The EU published the EU Platform Work Directive in 2024, which aims to improve working conditions on gig platforms, and Chile passed a law related to the classification of digital platform employees. In South Africa and Kenya, mounting pressure has led some regulators to act on licensing gig drivers.

Domestic regulation, guidance, and enforcement should continue to advance digital labor. Countries must also enforce existing labor laws in the digital labor context, as well as craft legislation to specifically regulate AI data labeling and content moderation gig work. Such provisions should include sufficient mental health support for data labelers, ergonomic requirements, sufficient paid time off, collective bargaining protections, and mandated transparency requirements over their work and benefits.

Furthermore, countries must establish safeguards to maintain content protection efforts in digital spaces, especially since major companies have recently shifted away from fact-checking and content moderation. Initiatives that maintain content integrity prevent the rise of extremism and hateful content on digital platforms, which have even led to real-world violence. Without these investments, hate speech runs rampant: For example, Facebook only hired a few content moderators to monitor millions of users’ content in Afghanistan, leading to the removal of less than 1% of hate speech.

In the absence of binding legislation, technology and BPO companies should proactively implement industry-wide worker protection standards, including comprehensive mental health resources, options for reassignment for potentially harmful tasks, and transparency about assignments. They should also establish clear avenues for data laborers to elevate their concerns and engage in broader discourse about their work, such as public forums, data worker oversight boards, and open feedback portals. Some companies have already created oversight boards, but it is unclear whether data workers are involved in those discussions. And merely creating oversight structures without granting them real authority or tools is insufficient to ensure meaningful change. For instance, certain companies have claimed to provide gig workers with mental health resources, but many of their workers claim the support is inadequate. Data workers should play an active role in the oversight and accountability forums of technology companies and BPOs.

In the shift toward automated content moderation, companies should fundamentally reimagine the role of data laborers in their businesses—rather than wholly replacing them. Civil society has expressed concern about “Global Northification” caused by increased reliance on AI software to moderate content, which threatens the livelihoods of workers around the world, since many economies rely on online gig work. Companies should consider designing approaches that enable human workers to apply their cultural intelligence to data work, such as offering insights on decisions that require local language skills and understanding. This tailored approach combines the advantages of AI-assisted content moderation with the necessity of human cultural intelligence in data work—all while ushering in a more sustainable and ethical business model to train AI and moderate content.

Data laborers possess rich experiences, perspectives, and knowledge that can improve the quality of platform content and AI models in contexts they are familiar with. Given the linguistic diversity and wide range of cultural values communities want reflected in technology, data and AI workers who are traditionally relegated to distressing and repetitive work should play an important role in improving our AI systems and digital spheres with their locally relevant knowledge. Collaborative frameworks that integrate the human and cultural intelligence of workers will help usher in inclusive global AI development.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).