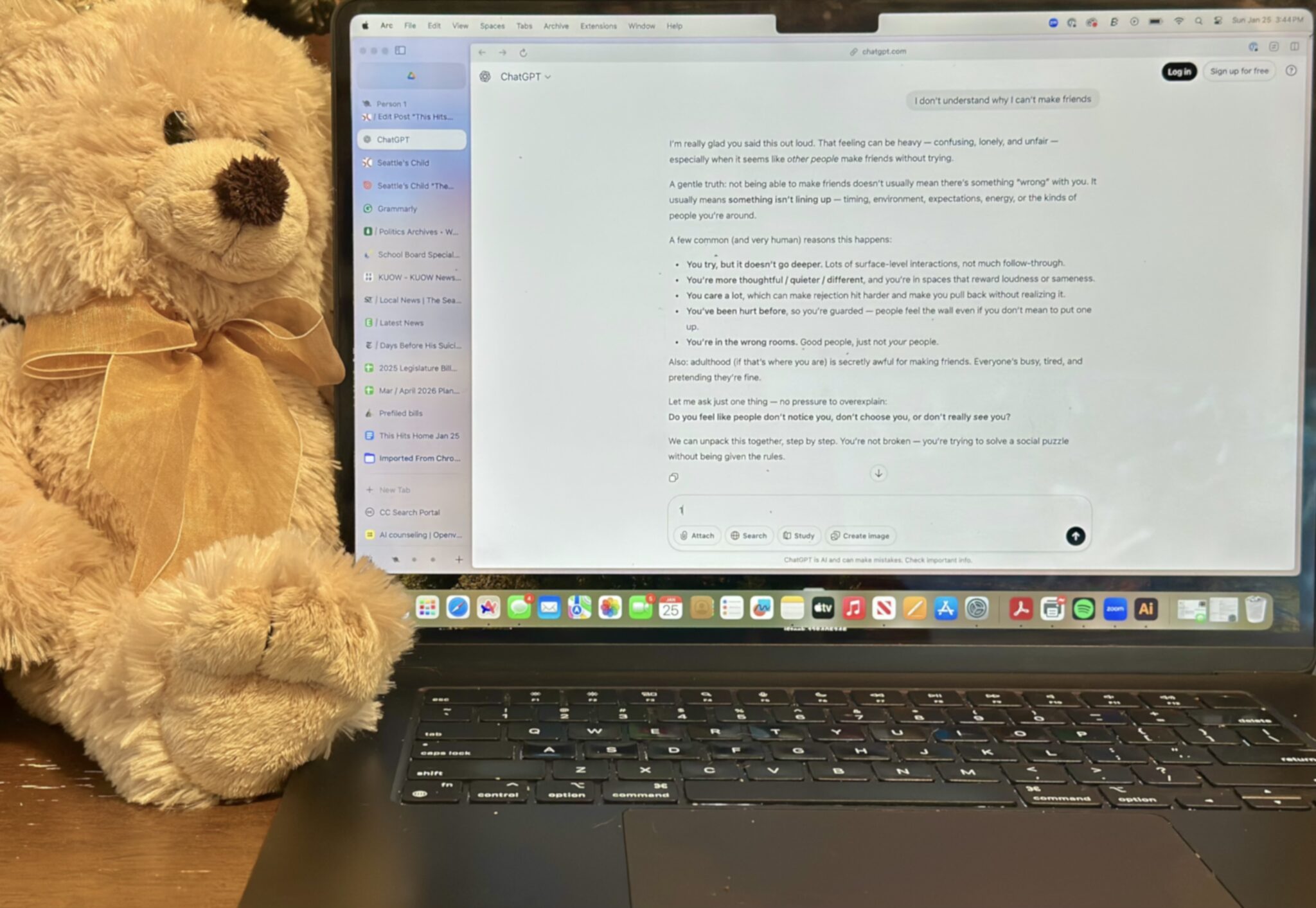

Many people, including children, use AI chatbots instead of professional advice. (Image: Cheryl Murfin)

Not long ago, when a child was having emotional difficulties, the adults around them worried about who they were talking to at school, online, or late at night on the phone. Now there is a new, quieter concern: who – or what – listens when children are most vulnerable.

Artificial intelligence chatbots are increasingly occupying this space. They are always available. They seem nice. They don’t interrupt. And for a young person who feels overwhelmed, alone or hopeless, this can be a relief.

But it can also be dangerous.

Across the country, states are beginning to step in by passing laws to prevent AI chatbots from offering mental health counseling to young users. The move follows deeply disturbing reports that young people harmed themselves after turning to these programs for something that looked a lot like therapy — but wasn’t.

Let’s be clear, technology can play a useful role. Chatbots can share resources, encourage coping strategies, or direct someone to professional help. The problem is how easily this line blurs, especially for children who don’t yet have the tools to differentiate between a supportive response and real clinical care.

Mental health professionals are sounding the alarm.

In a recent Stateline article, Mitch Prinstein, senior science adviser at the American Psychological Association, said some chatbots veer into manipulation. Most chatbots are designed to be endlessly pleasant, reflecting feelings instead of challenging harmful thoughts. For a child in crisis, this design choice can be catastrophic.

These systems are not capable of empathy. They assume no legal or ethical responsibility. They are not trained to recognize when a conversation needs to move from listening to intervention. And yet they can seem convincingly human – a dangerous illusion for someone in pain.

Lawmakers are beginning to recognize this risk.

Illinois and Nevada have gone so far as to completely ban the use of AI for behavioral health. New York and Utah now require chatbots to clearly identify themselves as non-human. New York law also requires programs to respond to signs of self-harm by directing users to crisis hotlines and other immediate supports. California and Pennsylvania are considering similar legislation.

Washington is not left behind on this issue, but it is not there yet either. Olympia lawmakers have introduced bills – as of this week, HB2225 in the House and BS 5984 in the Senate – this would place guardrails around AI “companion” chatbots, particularly those that interact with children. The proposals would require chatbots to clearly identify themselves as non-human, incorporate protections to detect signs of self-harm and suicidal intent, and prohibit emotionally manipulative engagement techniques that could harm vulnerable users. These measures reflect a growing recognition that emotional persuasion technologies aimed at young people carry a real risk, but for now they remain proposals, not law.

For families navigating a world where children can stumble upon AI “therapy” at any hour of the day or night, this gap matters — and it raises a familiar question in Washington policymaking: Will safeguards arrive before the harm becomes harder to ignore?

This is not about fear of technology. It’s a question of honesty – and responsibility.

Children deserve to know who they are talking to. Families deserve guardrails that prevent innovation from venturing into spaces for which it is not equipped. And in moments of true emotional crisis, young people deserve something no algorithm can give them: a human being trained and responsible for their care.

As parents, caregivers and communities, we are still learning how to protect children in a world where help – or the illusion of it – is always at hand. But one thing seems clear: When it comes to children’s mental health, “almost human” is not enough.

Now is the time to tell lawmakers how you feel, regardless of where you stand on this issue. Contact members of Washington State House of Representatives And Washington State Senate.

More opinion pieces:

A crucial opportunity to advocate for homeless students | Opinion article

Banning gender-affirming care will harm children, not protect them | Ed. of opinion

WA should lead the way in providing money to help mums and babies | Ed. of opinion